Before anything else. This article is only a snippet of what constraint-led approach is. If you want to understand more in depth the underlying mechanims of this approach and more examples on how to apply it, I highly recommmend checking out my eBook: Teaching Sports: An Essential Guide for Coaches and Trainers in which I discusss CLA and other methods in depth.

The gardener cannot actually “grow” tomatoes, squash, or beans – she can only foster an environment in which the plants do so.

– Stanley McChrystal

This quote by Stanley MacChrystal nicely encapsulates the idea of constraint-led approach. In this approach, the main goal of the coach is to foster an environment in which the athletes can grow. The coach is the designer, an engineer.

Constraint-Led Approach (CLA) is definitely my favorite strategy. You might be familiar with some of those concepts, but I would like to invite you to fully embrace this approach as it has been demonstrated to be more effective than traditional coaching. This approach will fundamentally change your role as a coach. You will move from being a “corrector” of movements to an architect of learning experiences

The Philosophy: Let the Constraints Be the Teacher

At the heart of the Constraint-Led Approach (CLA) lies a powerful idea:

Every movement an athlete makes is a solution to a problem.

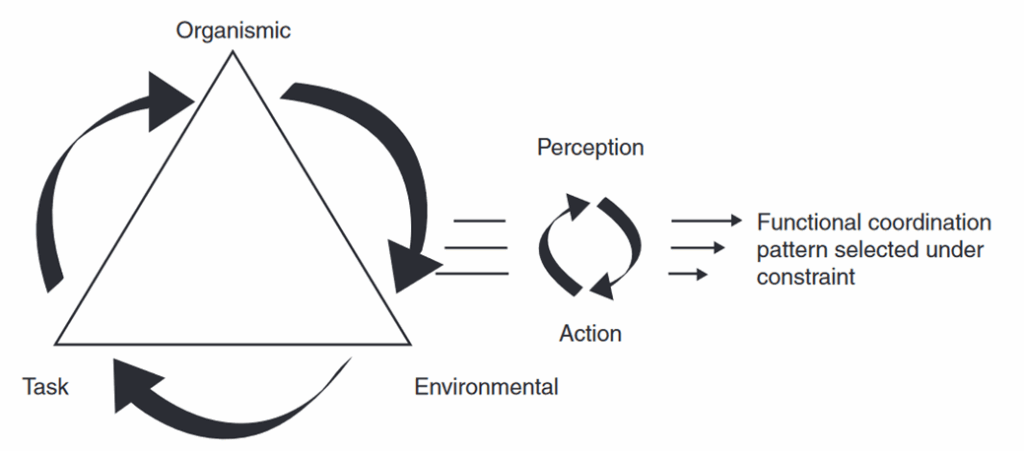

Rather than prescribing the “correct” technique, CLA invites athletes to explore and discover optimal solutions through experience. These solutions emerge from the dynamic interaction of key forces—known as constraints. Instead of instructing the athlete on what to do, coaches design problems—drills and scenarios—that naturally guide the athlete toward effective movement patterns. In this way, the environment becomes the teacher.

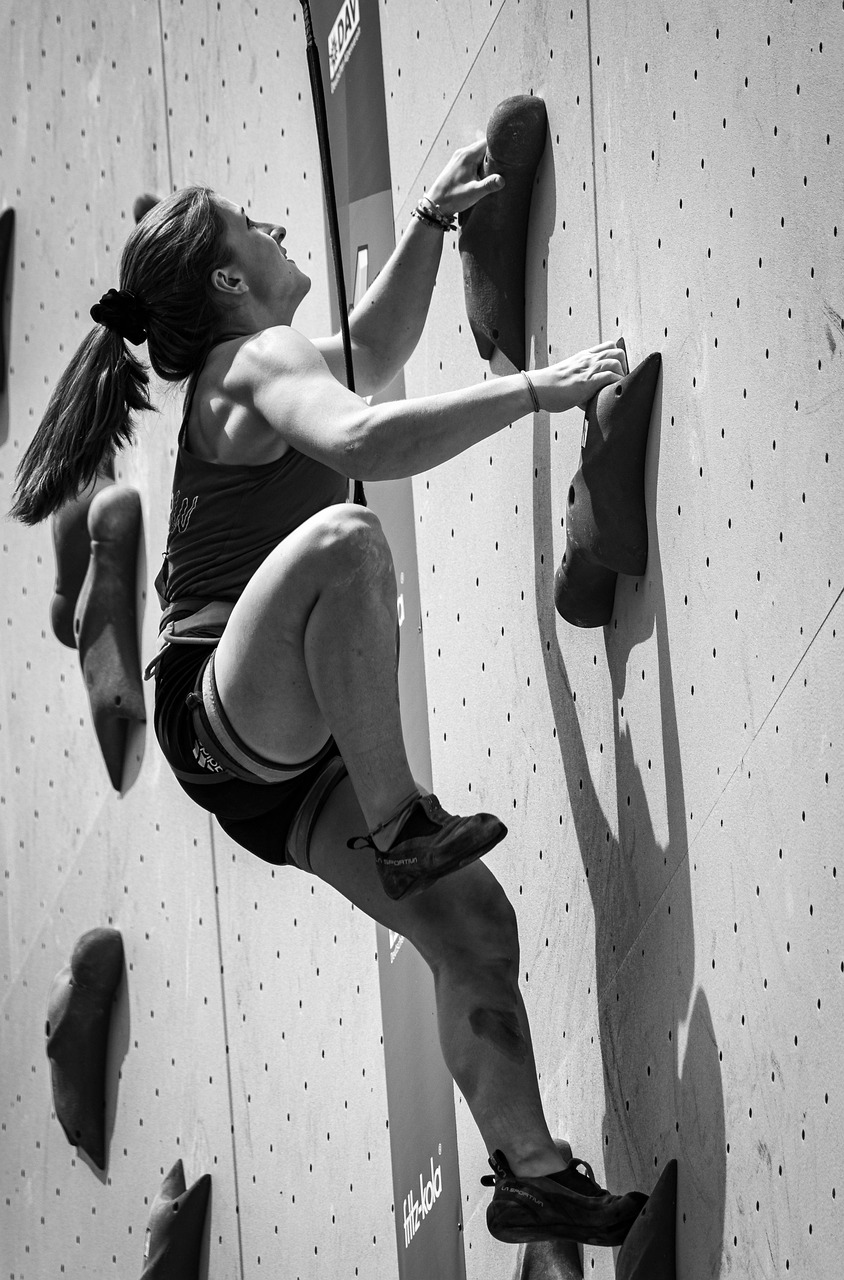

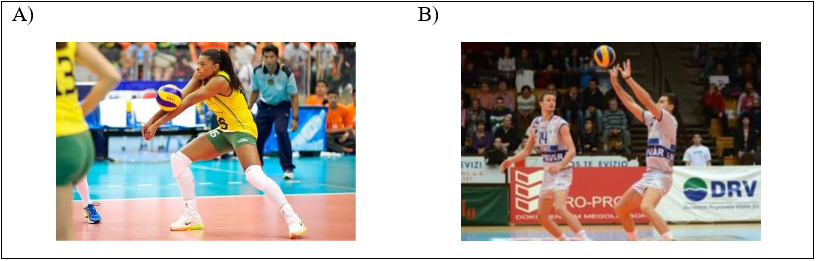

The motor system doesn’t understand verbal commands in English, Spanish, or any other language. It understands constraints. It responds to affordances—opportunities for action—presented by the environment. By manipulating constraints, we speak the motor system’s native language, allowing learning to emerge organically. Since the role of constraints is key in applying CLA, the coach should be an expert on understanding how constraints affect behavior. For instance, in volleyball, players usually receive serves using two distinct techniques, the underhand and overhead pass (Figure below). In that situation, the position of the ball (constraint) in relation to the position of the body (constraint) makes the affordance for using either technique more or less likely. If the ball is usually at head height, players are more likely to use the overhead. If the ball is lower, players are more likely to use the underhand technique.

The Coach’s Role: Designer of Learning Environments

In CLA, the coach is not a teller of truths but a designer of discovery. Their role is to:

- 🔍 Observe behavior and identify which constraints are shaping it

- 🧩 Modify constraints to encourage exploration of new solutions

- 🧠 Understand how perception and action are coupled in context

- 🛠️ Create representative learning environments that mirror game demands

Feedback in CLA: Less Telling, More Guiding

Feedback in CLA is not about correcting errors—it’s about guiding attention and amplifying information that helps athletes become more attuned to the environment. Effective feedback strategies include:

- ❓ Asking questions: “What did you notice about the ball’s height?”

- 🔄 Encouraging reflection: “What felt different when you adjusted your stance?”

- 🧭 Highlighting affordances: “Did you see the space open up on the left?”

- 🧪 Prompting experimentation: “Try adjusting your timing and see what changes.”

Rather than giving prescriptive cues, the coach helps athletes become better problem solvers by fostering awareness and adaptability.

The Three Types of Constraints: Your Coaching Toolkit

Think of these three constraints as the dials you can turn to shape the learning environment. I will give you some examples so you can have a better understanding how you can manipulate those constraints in your practice to achieve your desired goals.

1 – Task Constraints

Task constraints are the elements of practice that you, as the coach, control most directly. They include the rules, goals, equipment, and task conditions you design to shape how athletes interact with the environment. By adjusting task constraints, you create specific challenges or affordances that guide players to discover effective solutions.

For example, you might modify scoring rules to reward particular behaviors, change the size or weight of the equipment to emphasize certain movement qualities, or adjust the number of players to create different tactical demands. Task constraints are powerful because they set the boundaries of the activity while still allowing athletes freedom to explore within them.

2 – Individual Constraints

Individual constraints are the unique characteristics of each athlete that shape how they perceive and act in practice situations. They include physical attributes (such as strength, height, body composition, flexibility), perceptual abilities, cognitive skills, motivation, emotions, and prior experiences.

These personal characteristics strongly influence how athletes interpret information from the environment and generate movement solutions. For instance, two players may face the same task constraint but adapt in very different ways because of their distinct individual constraints. Understanding and respecting these differences is essential for designing effective learning environments that are challenging but attainable for each athlete.

3 – Environmental Constraints

Environmental constraints are the external features of the surroundings that influence how athletes perceive information and act within a task. Unlike task constraints, which you can design directly, and individual constraints, which are intrinsic to the performer, environmental constraints often arise from the context itself. They include both physical factors—such as weather, lighting, surface properties, and space—and social factors, like the presence of spectators, teammates, or opponents.

Environmental constraints play a critical role in shaping behavior because they continuously interact with the athlete’s perception and decision-making. For example, a wet field changes the traction underfoot, demanding adjustments in balance and foot placement. Bright sunlight can affect visual perception and timing. The noise of a crowd may impact focus or increase arousal levels.

Concluding Remarks

Just as a gardener fosters the conditions for plants to flourish, the coach cultivates an environment where athletes can grow—not through control, but through care, curiosity, and design. The Constraint-Led Approach (CLA) offers coaches a liberating and powerful philosophy: one that values exploration over instruction, adaptability over repetition, and learning over telling.

By embracing CLA, you transform your role from a commander of movement into an architect of opportunity. You stop searching for the “perfect technique” and begin crafting spaces where athletes can find their own optimal solutions. You stop correcting and start guiding. You stop teaching what to do and start shaping why and how they learn to do it.

🏗️ Constraints are not limitations—they’re invitations.

🧠 Movement is not memorized—it’s discovered.

🌎 The environment is not neutral—it’s a co-teacher.

If this resonates with you, I encourage you to dig deeper and reflect on how your coaching practice might shift by truly adopting the CLA framework. The ripple effects on athlete development, confidence, and autonomy are profound—and your role as a coach becomes not just more effective, but more meaningful